Trend Culture Engineering Desires

In my last post, I touched on adding variety not just to the information I consume, but also to how I consume it and the platforms I spend most of my time on. Over the last two months or so, one of my friends really got me hooked on video essays, and I’m not gonna lie…being able to just listen while getting things done around the house has been so satisfying.

The topic we discussed in August was overconsumption and how the media, companies, and influencers shape our desires and identities as we aim not only to reach a sense of self-actualization, but also to simply maneuver through life. This stems from last month’s discussion on how many persons don’t necessarily have a sense of self, but instead try on different identities (aesthetics) sold to them by the media.

Let me just preface this by saying that these are solely my opinions based on observations. Things are not black and white, and correlation doesn’t always imply causation. In other words, the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy (Latin meaning “(it happened) after it, so (it happened) because of it”) isn’t necessarily true.

What’s Your Aesthetic?

The concept of ‘aesthetics’ is nothing new. Fashion and trends have always been markers of cultural eras: think Y2K fashion or the pop trend wave of the 2010s, popularized by platforms like Tumblr, Instagram, Vine, and Snapchat.

But here’s what feels different now: the pace. With platforms like TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts dominating attention spans, trends don’t define years anymore; they shift monthly, if not weekly. The “soft girl” era, caramel makeup looks, old money vibes, bubble skirts, pilates girlies, the “clean girl” aesthetic…the list goes on.

This rapid cycle makes me wonder: Are people genuinely connecting with these aesthetics? Or are these trends simply well-designed marketing vehicles pushing products? Are we truly expressing ourselves, or are we shopping to affirm our worth?

My Intentional Shopping Era

I’ve been shopping less, not because I can’t necessarily afford the things I want, but because I’m trying to be more intentional with my purchases. And no, that doesn’t mean I won’t treat myself to nice things, because personally, I don’t think every purchase must be backed by some needs-based motivation. However, according to a research done by Nurhidayah Rosely and Sharifah Faridah Syed A Challenge Towards Sustainable Fashion Consumption: Fast Fashion And Impulsive Purchase Behaviour, 2023 they shared that, “according to Eco-Stylist (2022), fast fashion consumers purchase 60 percent more clothes compared to 20 years ago, and the consumption only lasts less than one year, meaning over 50% of the clothes end up in landfills”. So now I’ve been asking myself the harder questions:

- How many tumblers does a girl really need? (I have a lot—maybe too many.)

- How many pairs of shoes are actually necessary? (I went through my collection the other day and found shoes from three years ago that have never been worn.)

Do Your Research

This brings me to my next point—what I’ve realized about overconsumption is that it feels like an endless loop. We’re pretty much in a system that was designed to be hard to escape.

For example, we’re told to shop healthily, but the prices of those items often don’t match the reality of many people’s pockets. The truth is, the brands and products that seem more affordable are oftentimes not the healthiest and I’m starting to think they aren’t even trying to be.

Case in point: September is PCOS Awareness Month. I came across a video about a popular product substitute from a brand that many women with PCOS have been encouraged to use; only to find out that the company behind it is now facing a class action lawsuit for harmful side effects that may worsen the very symptoms these women were trying to reverse. A quick TikTok search showed this product had been pushed heavily as the perfect choice by content creators—packaged, of course aesthetically, with ASMR videos and crisp photos.

Moments like this remind me: it’s not on consumers to feel guilty; it’s on companies who put people at risk. Still, it’s a wake-up call for us to slow down, research, and ask ourselves: Do I really need this? Are there other alternatives?

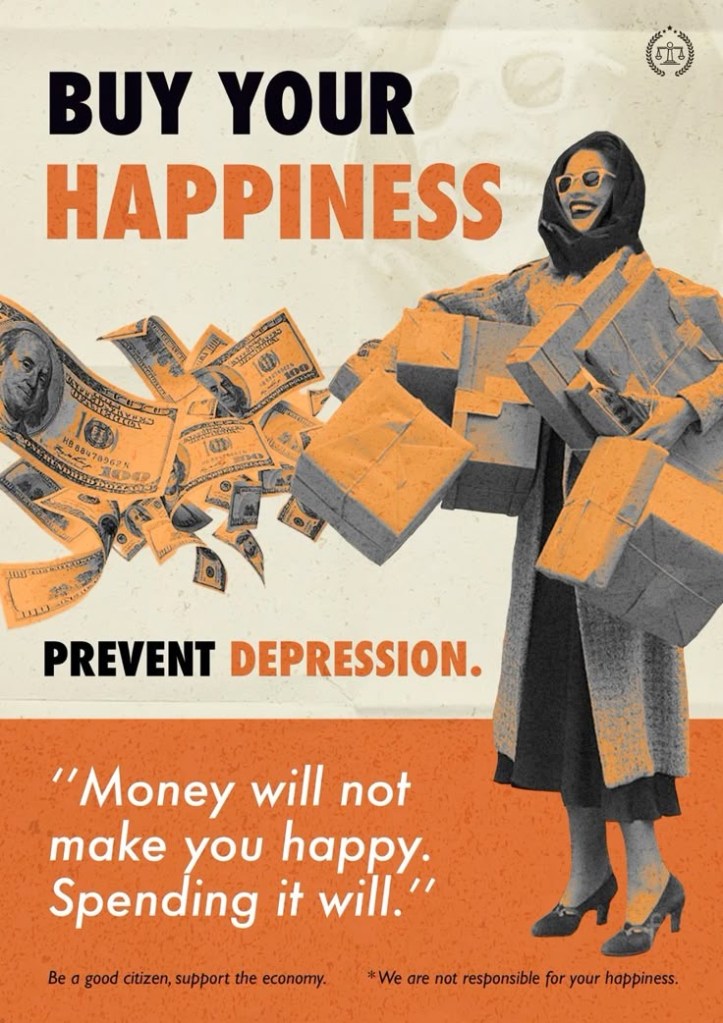

The Psychology Behind Overconsumption

Who doesn’t love the thrill of a package on the way? If I lived in the States, same-day shipping would be my guilty pleasure every time. That rush isn’t random, it’s dopamine shopping, and it’s addictive; because at the very least, it gives you something to look forward to.

Like I mentioned earlier, this isn’t a black-and-white issue. Many of us turn to shopping for different reasons. Maybe you grew up with strict financial restrictions or parents who didn’t think certain purchases were necessary. Maybe you’re learning to reward yourself more and for some, it’s about creating little pockets of joy to take their minds off everything happening in the world right now.

Then there’s the role of algorithms and micro-targeted ads. These are designed to exploit insecurities and create a sense of urgency: “You don’t want to miss this,” “Limited edition,” “Reverse [redacted insecurity here].”

The campaigns are almost always rooted in preying on the things we’re self-conscious about. Like, I promise, you don’t need that specific gym wear to get the best results.

Algorithms track what you search, watch, or linger on, then package it and sell it back to you. Add time-limited sales and product scarcity tactics, and you’re pressured into buying things even when you’re not ready to use them.

(Another case in point: I saw some cute shoes recently and was tempted to buy them, but every other TikTok was suddenly talking about the same pair. Spoiler: all the posts were tagged paid promotion.)

Social Media & Identity

Something we should constantly remind ourselves of is this: the internet, as it stands, was never originally created to help us make new friends, stay in contact, or communicate–at least not as its sole purpose.

As I referenced earlier, curated feeds and influencer marketing blur the line between authenticity and advertising. After reading this post, scroll through your social media feeds mindfully and notice how many posts are essentially just promoting products. The message is usually: buy this thing, it will “improve your life” whether it’s done overtly or subtly.

It’s often a letdown when I come across content that seemed like authentic life-sharing such as family vlogs, beauty content, lifestyle clips—only to realize they’re being used to sell something. Influencers lean into parasocial relationships, trying to be relatable, while influencing spending habits. And don’t get me wrong, I understand everyone’s trying to make their bag-after all I work in public relations. But sometimes, I just want to enjoy the content without feeling like someone’s trying to sell me something.

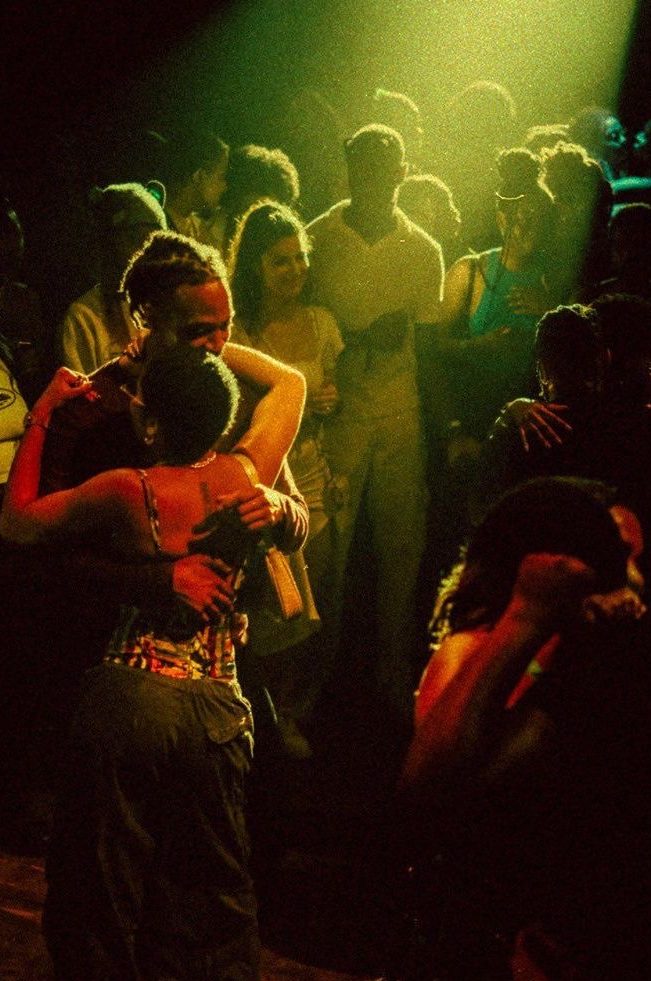

A Cultural Perspective

In a Jamaican context, material possessions often carry strong symbolic weight. Brand-name clothing, luxury cars, and imported goods are not just items; they’re markers of success, respect, and “making it.”

This ties into cultural values around outward appearances and the well-known saying, “fake it till you make it.”

Music plays into this too. Dancehall culture frequently celebrates wealth, designer brands, and high-consumption lifestyles. The music videos, lyrics, and street culture reinforce consumption as a way of gaining social recognition or aspiring to a certain lifestyle. Songs like “Money Speaks” by Popcaan and Teejay’s “Rags to Riches” just to name a few are perfect references. I honestly cant name how many songs this year alone has lyrics about luxury vehicles like the GLE, brands like Louis Vuitton, or “big house pon di hillside”—not to mention the casual glorification of “scammer” culture that over the last few years have been a recurring theme in Dancehall.

For many, consuming foreign products (especially American or European) reflects global connectedness and modernity, feeding into postcolonial aspirations of upward mobility and validation on the world stage.

But the downside? Cycles of debt, pressure on mental health (comparison, self-worth tied to materialism), and neglect of long-term financial planning. Add to that the already ridiculously high cost of living in Jamaica, and the weight of consumer culture becomes even heavier.

Opportunities for Change

We can’t change everything overnight, or maybe even at all- after all we do live in a capitalistic world that will always find new ways to dip into our pockets. Professor Jiang Xueqin phrased this perfectly in a recent video lecture “Consumerism is the Perfection of Slavery”. So as we continue to do what we can, there are small ways we can stop ourselves from losing our entire sense of self to overconsumption:

- Sustainable shopping habits: thrifting, clothing swaps, and buying higher-quality, long-lasting items.

- Support local or ethical businesses: keep money circulating in communities instead of fast-fashion giants.

- Personal challenges: try a “no-buy” month, or the “30 wears” rule (only buy clothing you can realistically see yourself wearing at least 30 times).

Final Thoughts

At the end of the day, consumption is part of life, but it doesn’t have to control us. Trends will keep coming, ads will keep targeting us, and companies will keep packaging identity into a product. But if we pause, ask questions, and shop with intention, we can create a healthier relationship with our consumption habits.

Question for you: What’s the last thing you bought that was more about how it made you feel than what you actually needed?

If you’ve gotten this far, I am now also on Substack Keepin It Crisp !

Leave a comment